Limits in a nutshell (Calculus Material 1)

Introduction to Calculus.

Introduction

So apparently, you’re supposed to do these posts for the entire material, not every week. Ooookay then. I’ll just copy the Day 1 and 2 post here as the limit definitive post, since it already covers all important points of limit. Okay bye!!!

What’s a Function?

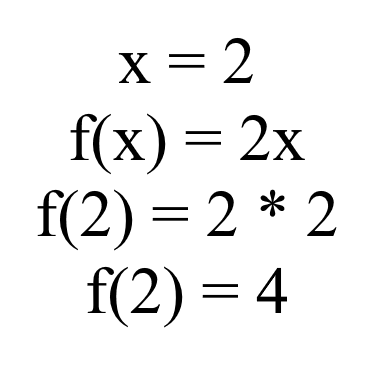

In very oversimplified terms, a function is basically where we substitute/transfer the value of x in f(x) into the right side (which is 2x in the picture above). The set of possible inputs (aka values of x in the example) is called the domain, and the set of possible outputs (results) is called the codomain.

The value of x we have is 2, then we substitute that value into the codomain’s x, which will result in f(2) = 2 * 2. Then we just multiply the numbers in the right side and we’ll get 4-Pretty straightforward. But Limit though… it’s a bit trickier than just substituting x’s.

How does Limit work?

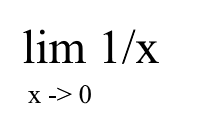

Limit’s fundamental theory is basically either trying to reach a certain point or a certain point where you can’t go any further beyond that point. Let’s take an example below :

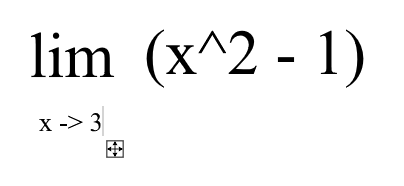

Limit of x = 3 in f(x) = x^2-1

Limit of x = 3 in f(x) = x^2-1

The example above wants to find what’s the limit aka what point it meets when x gets closer to 3. We can just substitute x inside the function with 3 and then get 3^2 - 1, which is 8. But… there is also the possibility of one of the answers being either infinite or not defined. These possibilities can happen when a 0 is usually involved, such as the example below :

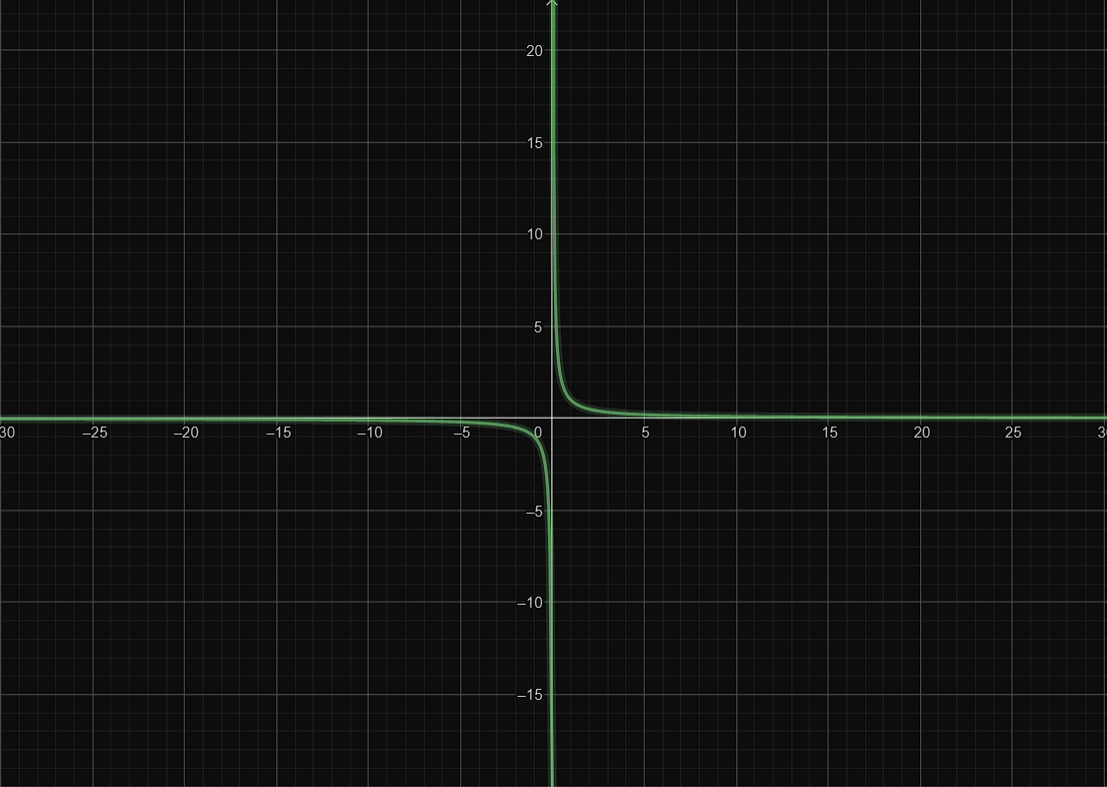

If we try to substitute 0 in the function, it will result with 1/0. Wait a minute, no numbers divided by 0 can result in a 1, which means it is not defined. How are we supposed to know what the actual limit value is? Well… if we try to place the function inside a graphic calculator, it would look like this.

In the picture above, we can see in the positive side (top right) that the higher the value of x, the lower the y but it will never reach 0, which is the x that we want to find the limit for. Same case with the negative side (bottom left). To find a limit at x = 0, the positive side (numbers after 0) and negative side (numbers below 0) has to meet at some point, but we can see that the number gets larger to infinity in the positive side, and smaller to negative infinity in the negative side. Thus, we can deduce that the limit doesn’t exist at all. That’s why sometimes we need to see the results from both sides (positive and negative) instead of blindly substituting x’s.

Other methods of solving Limits

Using graphs are not the only way to solve limit questions… Here, we will discuss other ways to find the limit without looking at graphs all day. There are 3 ways to do this, which is…

Direct Substitution

In Direct Substitution, all we have to do is well… substitute the value of whatever variable we have to the function directly. Here is an example!

\[\lim\limits_{x \to 1} (2x - 1)\]The x here reaches the value of 1, so we can just substitute that right to the function in the left, which results in (2 x 1-1) = 1. This doesn’t apply to every limit operation though, especially if it results in a 0/0. If this happens, we have to resort to other methods, such as…

Factoring

Some limit operations has functions in fractions (x/y). And as I’ve previously explained in my previous post, some can result in a 0/0. A possible solution is to factor the numerator/denominator (if applicable). Think of it as breaking down the function into smaller pieces. An example is :

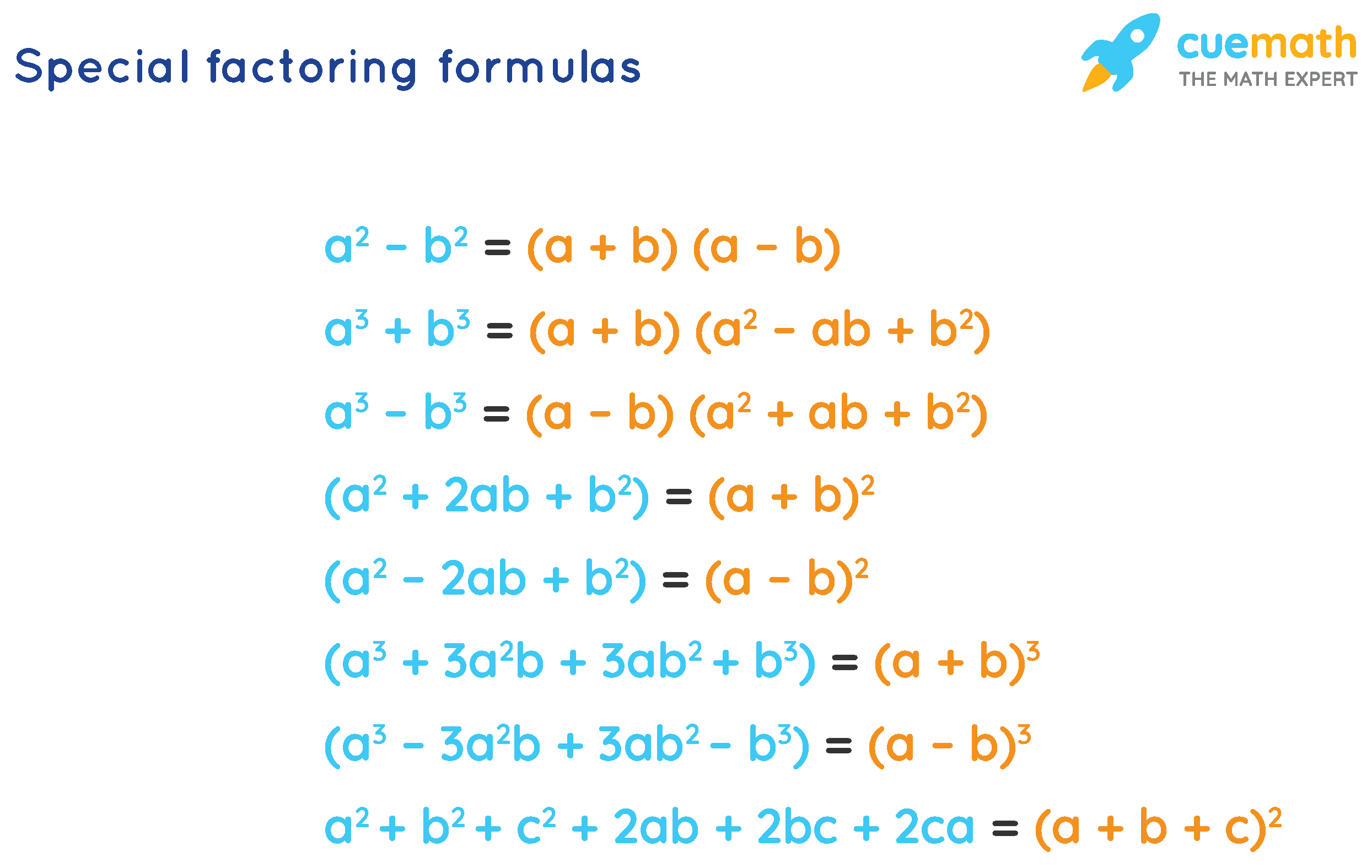

\[\lim\limits_{x \to 1} \frac{x^2 - 1}{x-1}\]If we directly substitute 1 into the function, it will always result in a 0/0. But… we can see that the numerator (x^1 - 1) can be further broken down with the formulas below

From the rules above, we can get that (x^2 - 1) can be broken down to (x-1) (x+1) / (x-1). We can see that there are 2 (x-1)’s in the fraction, so we can just cross/delete them out and then the result will be :

\[\lim\limits_{x \to 1} \frac{(x+1)(x-1)}{x-1}\] \[\lim\limits_{x \to 1} \frac{(x+1)\cancel{(x-1)}}{\cancel{x-1}}\] \[\lim\limits_{x \to 1} (x+1)\]Now, we can directly substitute 1 into the function, which will result in 2. There is another way other than factoring which is significantly harder depending on which formula you use. Introducing, derivatives (in the next definitive post though, not here.)!

Conclusion

Limits are basically where the positive side (numbers after x) and the negative side (numbers below x) meet. Sometimes it could have a result, or simply have no result at all. We explored three main ways to solve limits, which is:

- Manual Graphic - Don’t do this unless you have too much time to spare.

- Direct Substitution – The easiest method as long as it doesn’t lead to 0/0.

- Factoring – Useful when the function can be broken down.

If I’m wrong, feel free to give a feedback on why I’m wrong. Thank you for reading my post!